Part 3: Santa Cruz’s Crisis Is Unique

You know it, we know it: Santa Cruz is in dire straits when it comes to housing availability and affordability. And while that many-layered crisis is a tragic national trend, Santa Cruz’s straits are more dire than almost every other small housing market in the country. Why are we so uniquely stuck? 🚢

Santa Cruz’s Unique Stuck-ness

In 2020, all five least affordable small housing markets were in California (as well as the least affordable metro areas). Salinas sat at the very bottom, where only 10.9% of homes sold were affordable to families earning the area’s median income of ($75,800). Next up was Merced. In third place for Most Miserable Housing Opportunity Index: the Santa Cruz-Watsonville area.

No one—especially after 2020—can predict the future. In fact, many are wondering what long-term effects the COVID-19 pandemic will have on housing markets. But we can look at recent history to give us a picture of where Santa Cruz currently stands and what makes our local situation unique.

This graph from 2018 data presented by the Monterey Bay Economic Partnership (MBEP), shows just how far below the national average our area is when it comes to housing accessibility for the average family.

We talked with Santa Cruz City Councilmember Shebreh Kalantari-Johnson, who has been a prominent new voice on Council when it comes to housing development and revisioning a more livable Santa Cruz.

“I think it’s really exciting that some of my first votes as a City Councilmember were on some exciting housing developments,” Kalantari-Johnson said.

🚢 Development may be on the horizon, but like the Ever Given in the Suez, we (California in general and Santa Cruz in particular) have gotten so jammed that it’s going to take quite the tugboat to extract us from this crisis. Let’s look at just how jammed we are.

Look forward to more from that insightful interview and others next week.

“Let’s Do The Numbers” (Kai Ryssdal Voice)

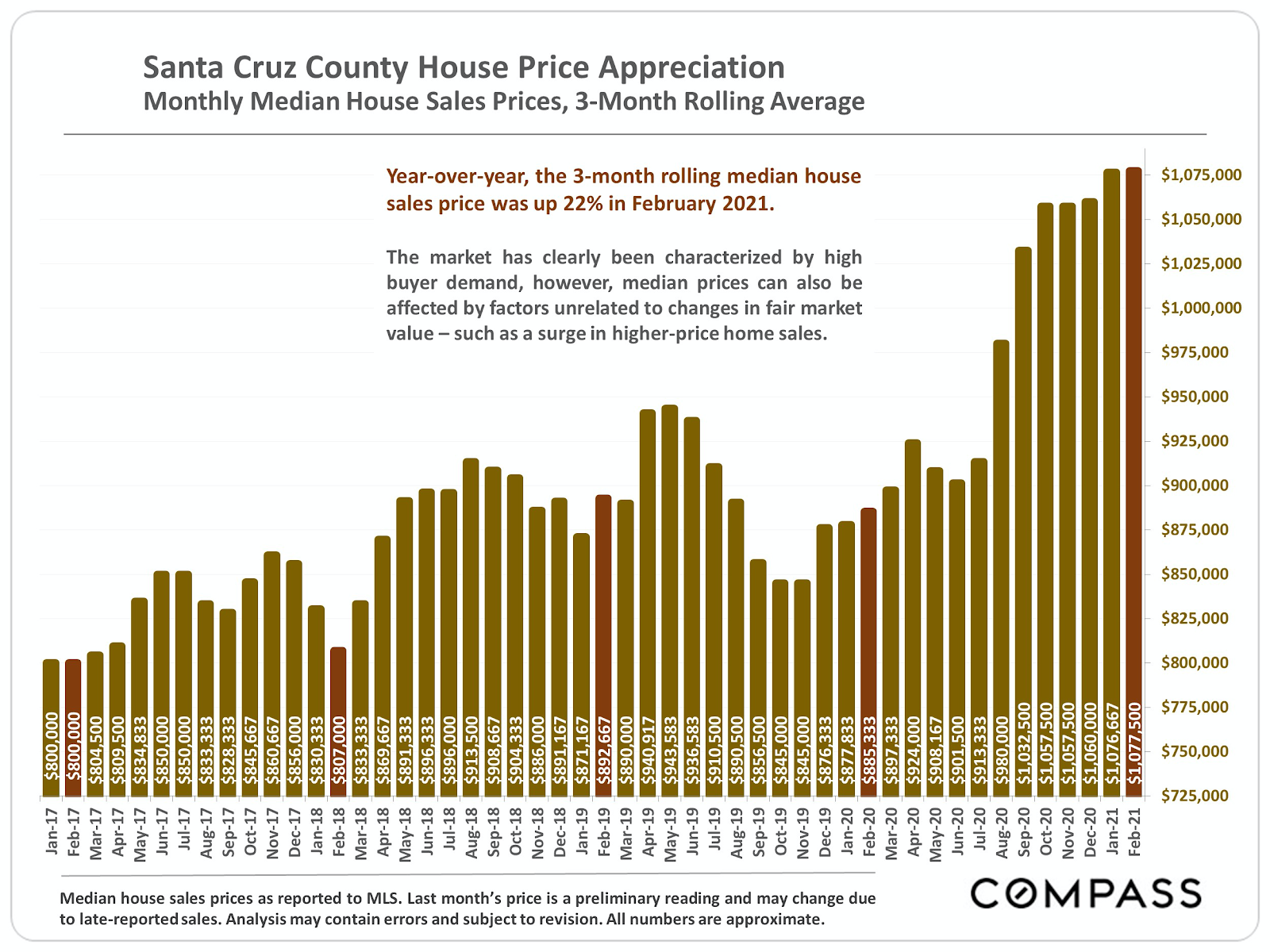

Median home value in California spiked in 2005, when they hit above $1 million for the first time. Santa Cruz County median home values mirror that pattern, though they didn’t quite reach that million-dollar mark back then. Directly after that, values dropped drastically until bottoming out in the depths of The Great Recession, around $500,000. Home values have been inching their way back up since then and now rest somewhere around $1 million.

Who’s Buying?

Our team (spearheaded by data wizard Adrian Dolatschko, who analyzed data from SCCAR), sifted through treasure troves of data to look more acutely at home-buying trends. Where were the most sales being made? Where were prices increasing most drastically?

Between 2016 and 2020, Santa Cruz had the highest home sale volume, and Aptos showed the largest recent fluctuation in homes sold. La Selva Beach and Los Gatos also had recent spikes and have some of the most expensive properties. Otherwise, unit sales volume has largely been constant to decreasing.

As for home price, the average Corralitos sale price has increased by over 150% since 2019. La Selva Beach and Scotts Valley have also seen large increases within the pandemic going far beyond the usual trend line.

Realtor data shows that 52% of homes purchased in 2019 were purchased by buyers with local zip codes. 48% of buyers had out-of-town zip codes. Of those 48% of buyers, 24% bought houses costing $2 million and over. Are ocean-front houses valued at over $2 million really to be considered part of the local housing inventory?

While it’s certain that the price of average-family homes are inflating beyond the means of any “average family,” home-buying trends show us that a lot of the incoming high-capital homebuyers aren’t scooping up the houses that average families want.

Live Here, Work Here?

Infographic from the Monterey Bay Economic Partnership (MBEP), Monterey Bay Region Housing Story, Accessed March 20, 2021.

As reported by MBEP in 2018, 61% of Santa Cruz County renters are spending at least a third of their income on rent. And 41% of housing units in Santa Cruz County are renter-occupied. That’s a lot of Santa Cruz County residents whose paychecks are being eaten up just by rent.

Between 2011 and 2015, California median rent hovered around $2,200 until 2014, when it crawled its way up to the current ~$2,600. In Santa Cruz, rent prices took a quick, steep drop to just below $2,500 in 2013 and then an even more drastic upspring. By mid-2015, median rent in Santa Cruz County was about $3,000.

Unlike median home prices, which hovered nearby those of San Benito County, Santa Cruz median rent prices at leagues above those of nearby San Benito County, Monterey County, and California at large.

Where Santa Cruz County Residents Go To Work

There are a total of 116,800 employed residents of Santa Cruz County. Of those, 62,670 people are employed within Santa Cruz County, with 21,580 employed within the City of Santa Cruz City and 10,520 employed in Watsonville.

54,160 Santa Cruz residents are employed outside the county. And of those, about 29,900 Santa Cruz residents work in the Bay Area).

(Thanks to Carey Pico for helping us look at this Census data!)

While we weren’t able to find specific traffic data to accurately reveal how many cars travel over Highway 17 to work every day (our data wizard tells us that 2020 data won’t be available until 2024), most recent SCCRTC reports indicate that 20,000 commuters make that drive for work.

2018 Commute destination data show us where Santa Cruz resident are heading to work:

Santa Cruz County, 77%

Bay Area, 17%

Monterey County, 5%

Other Destinations, 1%

Bay Area commute destination by county:

Santa Clara County, 14%

Alameda County, 1%

San Francisco County, 0.4%

San Mateo County, 2%

(Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Samples; Analysis by Beacon Economics)

2019 data shows that even more Santa Cruz county residents were working locally.

From the 2019 State of the Workforce report for Santa Cruz County, prepared by Beacon Economics. Accessed March 30, 2021.

Among residents age 25 and above who work, the average (both mean and median) wages of those who work in the Bay Area are at least double the average wages of those who work within Santa Cruz County.

While Santa Cruz County’s biggest employer is UCSC, a 2018 Santa Cruz Workforce Development report perfectly states the dilemma of talent and employment in the area:

“The region faces high turnover and low retention rates due to cost of living. In fact, many employers invest in training workers for higher-skill, higher-wage positions, but once these workers have gained experience and training, they often leave the region.”

A Multi-Tiered Crisis

Nearly every expert we talked to spoke about the multiple layers of the housing crisis. It’s not just young professionals and families who are suffering when they can’t find desirable houses within their prices ranges. It’s not just renters who are among dozens of desperate applicants to over-priced apartments and unsanctioned ADUs, where they’re paying $2,000 to have termites and mold on their windowsills.

Among those hit hardest by this quagmire are low-income renters pushed out of homes completely, and elderly adults who are aging out of single-family houses with nowhere affordable and accessible to go.

The fact is this: Santa Cruz is more accessible to those who earn higher wages as median home price increases. And higher wages are now found in the Bay.

But remember—and we banged you over the head with this in Part 2, but it bears repeating again and again—a housing crisis only happens when there is a housing shortage. A housing shortage happens when development is stalled, sluggish, opposed, or blocked altogether.

So we want to add a layer of truth and perspective to the cut-and-dry data we just flooded onto your screen.

Consider this: how does framing the housing crisis we are experiencing as an invasion of tech move us forward? Or does it dehumanize those residents trying to build happy lives for themselves while also simplifying the crisis in a way that is...less than helpful?

When we meet next week, it’ll be time for ideas, solutions, and advice from experts.

This is Part 3 of a 5 part series: Is Silicon Valley invading Santa Cruz.

Thanks to contributors: Monterey Bay Economic Partnership, Terri Mayall, Sibley Simon, and Carey Pico.